The environmental case for natural gas

This commentary is a preview of new and original analysis that will be published in the forthcoming World Energy Outlook 2017, released on 14 November, which includes a detailed focus on natural gas. This excerpt addresses some of the key findings relating to the environmental case for gas and, in particular, the issue of methane emissions from oil and gas operations. The authors are Tim Gould, Head of the WEO Energy Supply Outlook Division, and Christophe McGlade, WEO senior analyst.

The role that natural gas can play in the future of global energy is inextricably linked to its ability to help address environmental problems. With concerns about air quality and climate change looming large, natural gas offers many potential benefits if it displaces more polluting fuels. This is especially true given limits to how quickly renewable energy options can be scaled up and that cost-effective zero-carbon options can be harder to find in some parts of the energy system. The flexibility that natural gas brings to an energy system can also make it a good fit for the rise of variable renewables such as wind and solar PV.

There is very little dispute about the emissions associated with natural gas combustion. However, there is much less consensus over the level of direct methane emissions that can occur – whether by accident or by design – on the path from oil or gas production to final consumer. This is a critical issue for the long-term natural gas outlook: methane is a potent greenhouse gas and the uncertainty over the level of methane emitted to the atmosphere raises questions about the extent of the climate benefits that gas can bring. One aim of the forthcoming WEO-2017 analysis is to investigate the sources of this uncertainty and explore what actions can be taken to reduce emissions.

Gas has the edge on combustion emissions

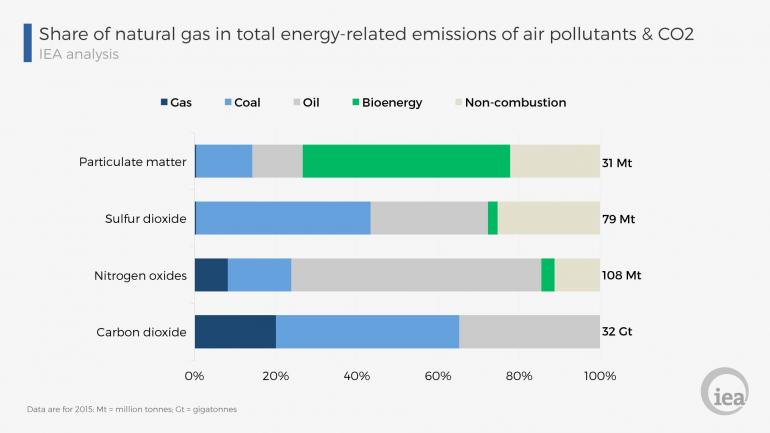

The emissions from natural gas combustion are well-known and show clear advantages for gas relative to other fossil fuels. CO2 emissions (per unit of energy produced) from gas are around 40% lower than coal and around 20% lower than oil. The edge of natural gas over other combustible fuels is reinforced when considering emissions of the main air pollutants, including fine particulate matter (PM2.5), sulfur oxides, mainly sulfur dioxide (SO2), and nitrogen oxides (NOX). These three pollutants are responsible for the most widespread impacts of air pollution, according to the WEO Special Report, Energy and Air Pollution 2016.

Gas combustion produces significant levels of nitrogen oxides (NOX), with around 10% of global NOX emissions coming from the use of gas. However, it produces virtually no SO2 emissions and negligible levels of PM2.5 (See figure below). Coal use dominates global emissions of SO2, oil products used for transport are the dominant source of NOX, while the combustion of wood and other traditional solid fuels are responsible for more than half of current PM2.5 emissions according to the latest WEO Special Report, Energy Access Outlook 2017.

The question of methane

These generally low-emission characteristics of natural gas help underpin its status as a relatively clean fuel compared to other fossil fuels, but that does not necessarily give gas a clean bill of health. One critical question is the extent to which methane emissions along the gas value chain negate the climate advantages of gas.

Before looking at this question, it is helpful to examine the issue of methane emissions more generally. The concentration of methane in the atmosphere is currently around two-and-half times greater than pre-industrial levels. This rise has important implications for climate change. In 2012, the latest year for which comprehensive data are available, global methane emissions were estimated to be around 570 million tonnes (Mt). This includes emissions from natural sources (around 40% of emissions), and from anthropogenic sources (the remaining 60%). The largest source of anthropogenic methane emissions is agriculture, responsible for around a quarter of the total, closely followed by the energy sector, which includes emissions from coal, oil, natural gas and biofuels.

In the WEO-2017, we estimate there were 76 Mt methane emissions from oil and gas operations in 2015, split in roughly equal parts between the two. These emissions came from a wide variety of sources along the oil and gas value chains, from conventional and unconventional production, from the collection and processing of gas, as well as from its transmission and distribution to end-use consumers. Some emissions are accidental, for example because of a faulty seal or leaking valve, while others are deliberate, often carried out for safety reasons or due to the design of the facility or equipment.

The large oil and gas-producing areas of Eurasia and the Middle East are estimated to be the highest emitting regions, accounting for nearly half of the total emissions globally, followed by North America. Averaged globally, our estimate of emissions from the natural gas chain (42 Mt in 2015) translates into an emission intensity for gas of 1.7% – that is the average percentage of gas produced that is lost to the atmosphere before it reaches the consumer.

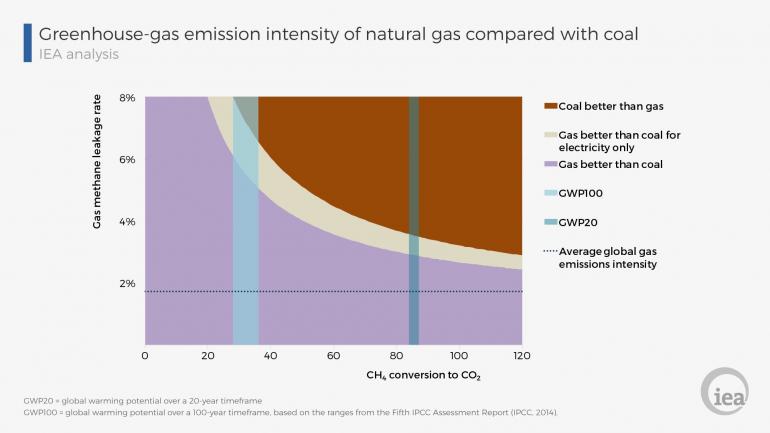

What does this mean for the lifecycle emissions of gas compared to coal? For this calculation, it is common to rely upon the “global warming potential” to convert methane emissions into a single CO2-equivalent term so that it can be combined with combustion CO2 emissions. Methane traps much more heat than CO2 (per unit of mass) while in the atmosphere but stays there for a much shorter time. This conversion is therefore not straightforward, most notably because it depends on what timeframe is considered. A tonne of methane is equivalent to between 84 and 87 tonnes of CO2 when considering its impact over a 20-year timeframe (GWP20) and between 28 and 36 tonnes over a 100-year timeframe (GWP100). Another consideration is that the conversion of natural gas into electricity tends to have a higher efficiency than coal, so emissions are lower for natural gas if given in terms of electricity produced instead of heat.

Despite these issues, taking into account our estimates of methane emissions from both gas and coal, on average, gas generates far fewer greenhouse-gas emissions than coal when generating heat or electricity, regardless of the timeframe considered.

What can be done?

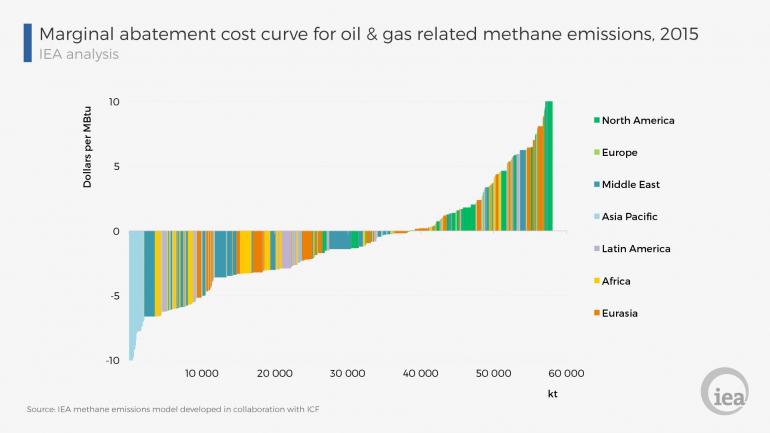

Even if natural gas is better than coal, this comparison sets the bar too low. The environmental case for gas does not depend on beating the emissions performance of the most carbon-intensive fuel, but in ensuring that its emission intensity is as low as practicable. In addition, a key reason to tackle methane emissions from oil and gas operations (compared to other anthropogenic sources) is that in many cases there is a readily available path to market for the captured methane to be sold. If the value of this methane is greater than the cost of the technology to capture it, it would be possible to avoid the emissions of a potent greenhouse gas while simultaneously generating a profit.

To explore this issue in detail in the new Outlook, we developed first-of-a-kind global marginal methane abatement cost curves. These curves describe the reduction potentials, and costs and revenues of measures, to mitigate methane emissions globally (one example is shown in the figure below for emissions abatement in 2015). Using these curves, we estimate that it is technically possible to avoid around three quarters of the current 76 Mt of methane emissions. Even more significantly, around 40-50% of current methane emissions could be avoided at no net cost. The cost of mitigation is generally lowest in developing countries in Asia, Africa and the Middle East. But in all regions reducing oil and gas methane emissions remains a cost-efficient way of reducing greenhouse gas emissions compared with other mitigation strategies.

A compelling case for further action

If a high share of current emissions can be mitigated using measures that will pay for themselves from the methane recovered, why have these not already been widely adopted? Possible reasons include a lack of awareness about emission levels or the cost-effectiveness of abatement; competition for capital within companies with a variety of investment opportunities; insufficiently quick payback periods to clear the threshold for investment; and the possibility of split incentives (where the owner of the equipment does not directly benefit from reducing leaks or the owner of the gas doesn’t see its full value).

The benefit to overcoming these hurdles would be enormous. Implementing only the abatement measures that have positive net present values in the New Policies Scenario (the central scenario of the World Energy Outlook) would reduce the temperature rise in 2100 by 0.07 °C compared with the trajectory that has no explicit reductions. This may not sound like much, but it is immense in climate terms. To yield the same reduction in the temperature rise by reducing CO2 emissions would require emitting 160 billion fewer tonnes of CO2 over the rest of the century. This is broadly equivalent to the CO2 emissions that would be saved by immediately shutting all existing coal-fired power plants in China.

The technologies and approaches to address methane emissions from the oil and gas sector are available already today and there is a growing number of voluntary and regulatory efforts in this area. There are some signs of progress: the emission intensity of gas in the United States, for example, has been on a steady downward trend in recent years. But achieving these abatement measures will require a step-change in ambition, in an area where few countries have specific mitigation frameworks in place. The case for further action is compelling.

Gas demand grows to 2040 in all the scenarios of the WEO-2017. The pace of this growth will be determined by a range of factors, including the affordability of gas relative to other fuels and technologies, the policies that governments put in place, and the impact of an increasingly liquid and interconnected global gas market on investment and security of supply. It will also depend on the industry demonstrating credibly that methane emissions from oil and gas operations are being minimised.